Ambassador Cindy Courville, first U.S. Ambassador to the African Union, 2006-2008

In celebration of Africa Day 2021 and its 58th anniversary, we had the opportunity to interview Ambassador Cindy Courville, who served as the first U.S. Ambassador to the African Union (AU) from 2006 to 2008. Originally founded in 1963 as the Organization of African Unity (OAU), its primary mission was to decolonize the African continent. Now known as the African Union (AU), its mission since July 2002 has been “to promote economic advancement among African nations, Africa’s growth and economic development, and increase cooperation and integration of African states.”

Over the last several decades, the United States has fostered a strong bipartisan, bilateral relationship with the AU and its African member states, partnering on issues like global health, economic ties, youth and education, agriculture, and more. Ambassador Courville’s long and illustrious public service career includes decades of experience shaping and transforming U.S. policy in Africa while serving with the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Council, and as Ambassador to the AU based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

AMB COURVILLE: This was a pivotal moment in the history of the African continent marking a transition point in time. The Organization of Africa Unity had accomplished 99% of their mission to decolonize the Continent—and now they wanted to launch an organization whose mission embraced a political, economic, security, and humanitarian component. An ambitious task to undertake, but these African leaders had a vision.

President Bush at the time was very much engaged with members of the Continent and saw the appointment of U.S. Ambassador and creation of an observer mission to the AU as an opportunity for the United States to, what we call, “lift” … No other observer country had a dedicated ambassador to the African Union. No matter if we were the first or not, the United States saying, ‘we recognize this institution,’ was fundamentally important, not to legitimize but to say ‘we are standing next to you’… What better respect could we show for the Continent than to have a dedicated ambassador—the same way we have a dedicated ambassador to the UN, to the EU, and to NATO.

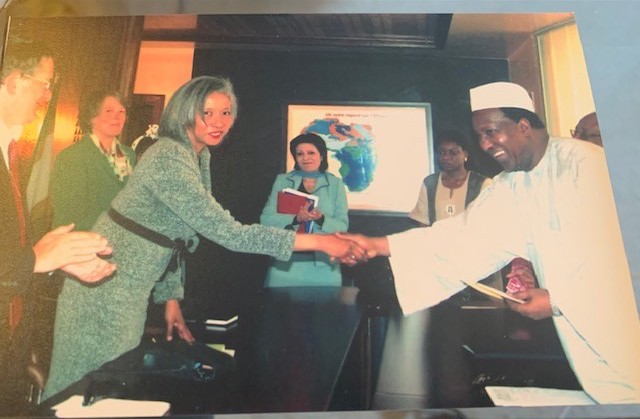

Ambassador Cindy Courville presenting her credentials to the Chairman of the African Union.

Photo credit: Ambassador Courville

AMB COURVILLE: It was surreal and daunting at the same time because I had to go through the confirmation process, and this was tougher than my dissertation defense! On a personal note, I was honored. I had a sense of responsibility that went beyond Cindy Courville because I was now representing the United States Government abroad, African American women, and all women. It was an opportunity to bring together my academic experience, my analytical experience, as well as a little bit of my Louisiana politics having grown up in a time of apartheid in the United States. I’m old enough to have ridden on the back of the bus, sat upstairs in the movie theaters, and gone into the backdoor of restaurants. While there were so many things that I was carrying on my shoulders I took comfort knowing that I was lifted on the shoulders of those who had come before me like my two enslaved great-great grandmothers, Caroline Brown and Melissere Melancon.

I was on the ground maybe not quite a month when Ethiopia intervened into Somalia in 2006. To have that Ethiopian intervention at the time was incredible. The question I was faced with was ‘how do we bring U.S. resources to support a peacekeeping mission in Somalia?’. Everything I was doing at that point was under scrutiny in my capacity as the U.S. Ambassador to the African Union by all of the Africans and by the rest of the world who were looking at what we, the United States, were doing, and why the U.S. was doing it.

AMB COURVILLE: Bringing corporate America in with Congress and finding a goal that goes beyond partisanship, beyond the bottom line and how much profit you can make, and [shows] that you can make a profit and still do good and that you can be from a different party and still engage. I think that’s so important.

I’ll start with PEPFAR because it was a medical Marshall Plan for engagement that saved so many lives…and has had a lasting impact on everyday lives… Dr. Fauci was on the cutting edge of HIV/AIDS…He had gone out to Uganda to one of the clinics there with the doctors. The interoperability of working together on things like a pandemic bring us together whether we want to or not, and we choose whether to step up or not.

From a policy perspective, economic engagement has to go hand in hand with political, health and climate change. We’ve not done enough on climate change. I’m concerned about education, not only from my own country but on the [Africa] continent as well. Brilliant people who are missing out; the potential is overwhelming… The intellectual capability of the Continent is not fully utilized. We cannot, as a world, as a people, not be a party to this and partners in this. I would hope on the economic front that we take AGOA, or whatever the next new name is, to the next level because to invest in that continent is good for Americans, Africans, and the world.

We cannot as Americans believe in the African continent more than Africans do. At the end of the day, we are Americans… But if you can have a win-win situation…we can work together as human beings to have a better world.

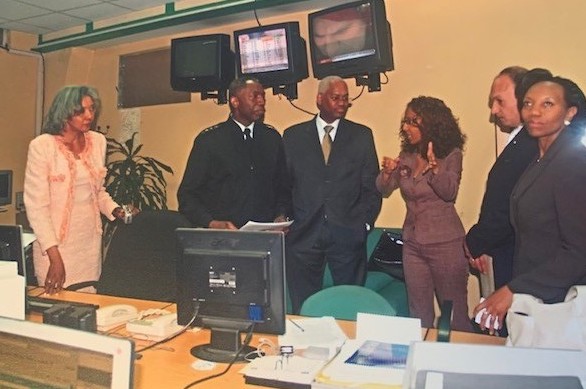

Ambassador Courville (left) with General Kip Ward (second to the left), the first U.S. AFRICOM Commandant Commander, meet with the Peace and Security Commander and other AU officials.

Photo credit: Ambassador Courville

AMB COURVILLE: Before World War I and II, the United States was a non-player in Africa, deferring to our European allies. It isn’t until after World War II that the U.S. made the decision to directly engage in Africa and not simply to defer to our European allies’ approach to Africa.

First, the Clinton Administration made the decision to implement economic policy engagement with African countries with the passage of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). Second, the Bush 43 Administration implemented a medical Marshall Plan with the launch of the President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (PEPFAR) to address the HIV/AIDS pandemic and made the policy decision to establish the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) that provided grants instead of loans for building infrastructure, like dams, roadways, and economic zones on the African continent.

Another important policy first for the Bush Administration was the establishment of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), which the Department of Defense talked about for almost 30 years and enhanced U.S. bilateral and multilateral defense and security in Africa.

Fourth, the Obama Administration launched the Power Africa Initiative, which increased the U.S. commitment to energy access in Africa. The next step I hope is that we pursue what President Obama talked about in terms of energy and most certainly climate change, which both Obama and Biden have embraced. So that means looking at new industries and how to engage.

There’s lots of work to be done in infrastructure development and economic engagement on the African continent. I believe that with incentives a continuation of MCC, as well as a transformation of AGOA, will makes it possible for American businesses to engage on the Continent. It is also important that change how we talk to American businesses about going to the Continent [in terms of] competition. The U.S. can do all it wants on this side of the table, but if there is not the political will of the African leadership and the willingness to put their own resources towards change, there will be no lasting change.

AMB COURVILLE: The optimism and the perseverance of the people on the Continent most certainly gives me hope…The youth, as well as those seniors like myself, still have so much to offer. Even when the United States stumbles, the people of the African continent and their leadership have always been willing to partner with us. Their graciousness and willingness to reach out to us gives me hope.