At the recent NATO summit, much time was spent discussing whether America’s allies spend enough on defense. At a time when many of today’s global challenges do not have military solutions alone – from pandemics like Ebola to refugees driven by famines and conflicts – how does the debate shift if we consider not just military spending but spending on global development?

Former-Defense Secretary Frank Carlucci once observed that “peace through strength” means more than military power, writing “President Reagan knew active diplomacy and strategic foreign assistance were essential to promoting freedom around the world, to making us and our allies safer, and to encouraging economic growth.”

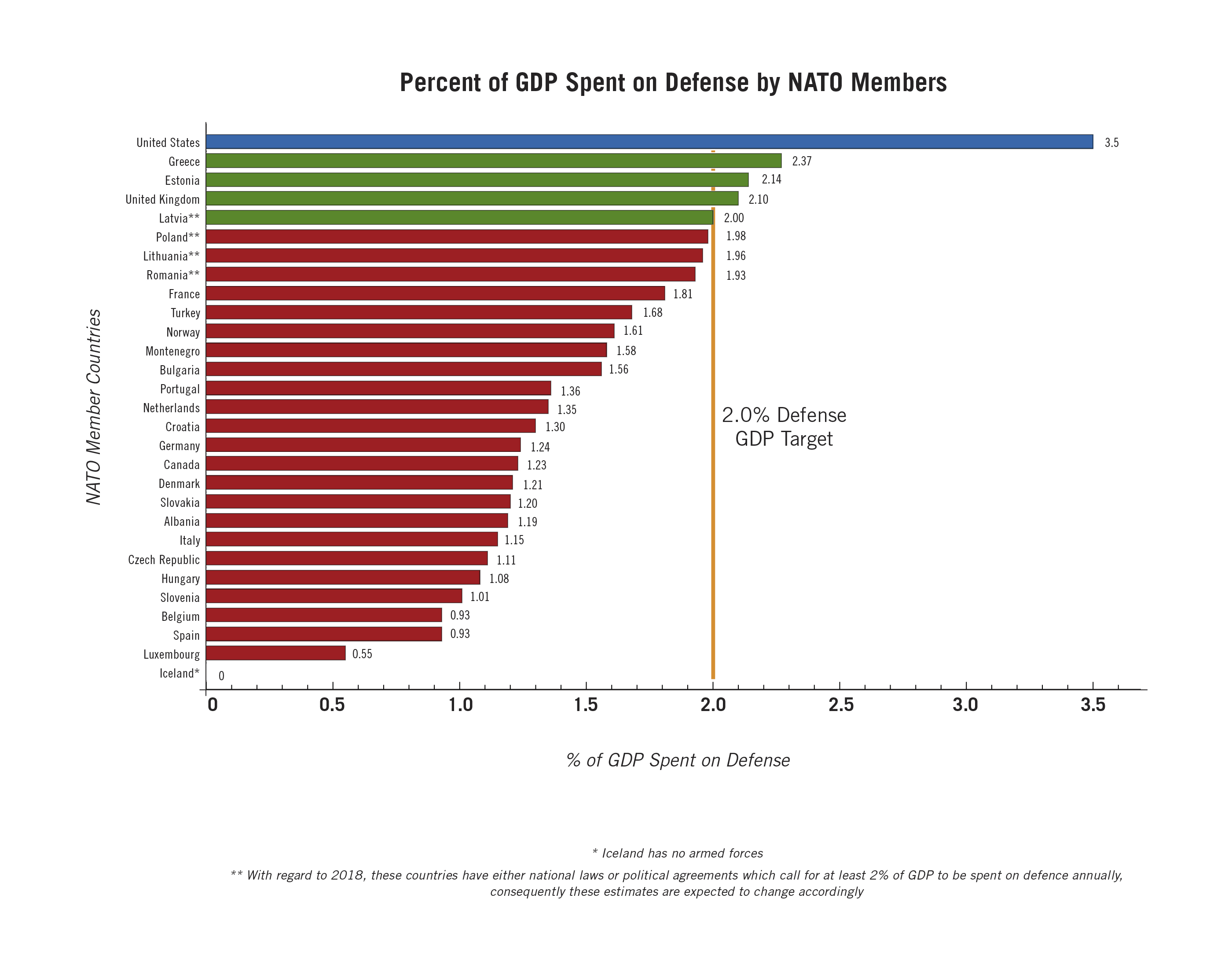

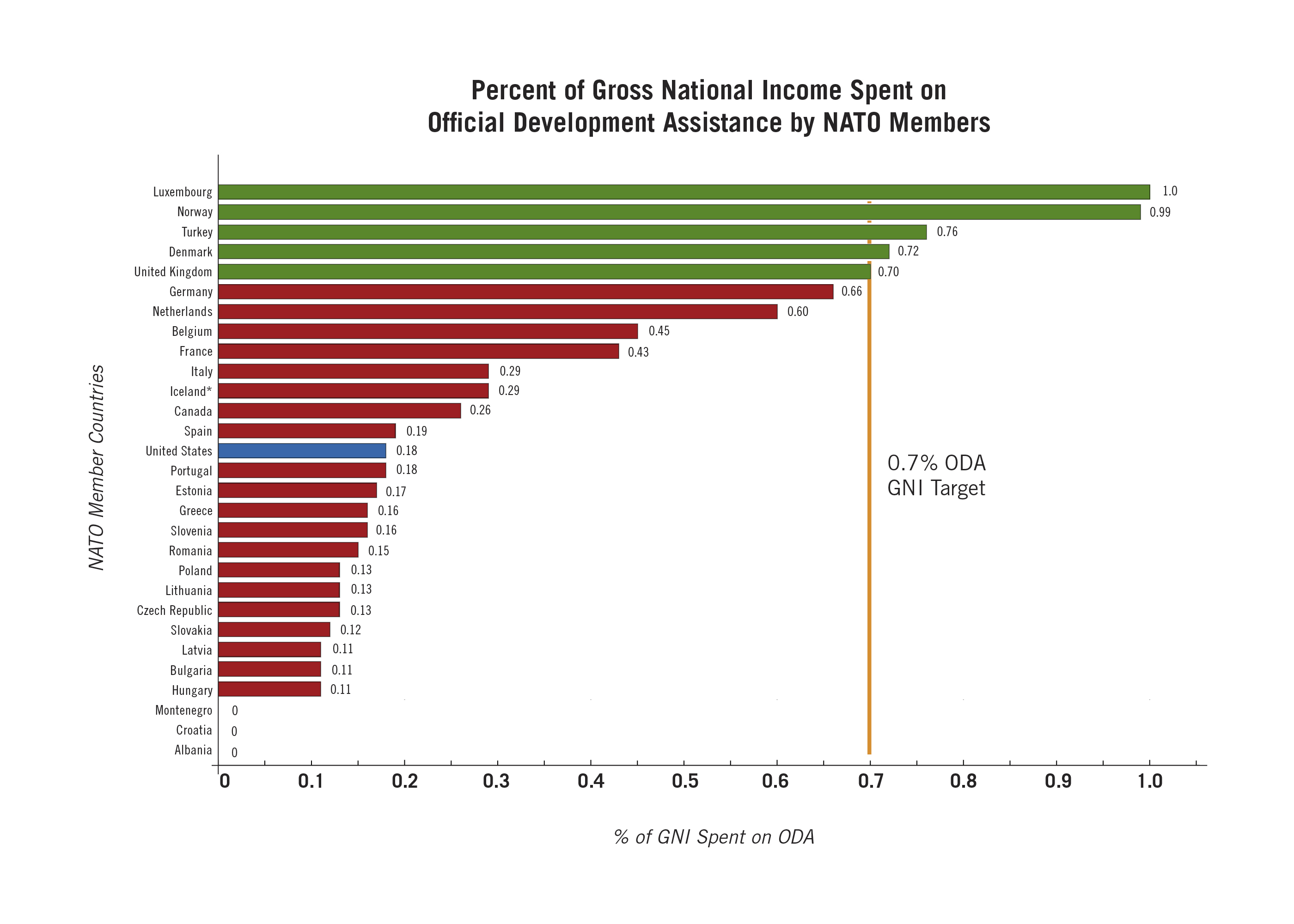

Just as NATO’s 2% target creates a benchmark for military spending, since 1970 there has been a widely recognized target for spending on official development assistance: 0.7% of gross national income. How do the two line up?

Comparing Investments in Defense and Development

The U.S. spends the most in absolute terms on both defense and development among NATO countries, and it is also by far the largest economy. Relative to GDP, the United States spends by far the largest percentage on defense among all NATO countries at 3.5% – but spends just 0.18% of gross national income on official development assistance. This makes it the 14th most generous country among NATO countries on development—in the middle of the pack.

Consider that the U.S. spends $35 billion on development while the United Kingdom spends $18 billion or roughly half, but America’s GDP is more than six times that of the U.K. It is striking that the United Kingdom is the only country that meets the 2% target for defense and the 0.7% target for development, especially against the backdrop of President Trump’s first visit as President this weekend.

Five NATO countries meet the two pledges. Those that meet the 2% pledge on defense are the United States, Greece, Estonia, the United Kingdom, and Latvia. (There is currently legislation in Romania, Lithuania, Poland, and Latvia that will require each nation to meet the 2% pledge). And those that fulfill the 0.7% development pledge are Luxembourg, Norway, Turkey, Denmark, and the United Kingdom.

The charts also underscore that, aside from the UK, the countries that meet the 2% GDP defense spending commitment actually spent less on development than the United States: Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania. Many of these countries have smaller economies, and they are closer to Russia so may perceive the military threat more directly than Western Europe.

A Comprehensive Approach to National Security

Chancellor Merkel made the point about the security contributions of investments in development last year at the Munich Security Conference, observing “When we help people in their home countries to live a better life and thereby prevent crises, this is also a contribution to security” (although Germany’s spending on official development assistance falls just below the 0.7% pledge).

For the U.S. to hit the 0.7% target, it would have to spend $137 billion on official development assistance a year, more than double the entire International Affairs Budget today. This is wildly unlikely to happen, but these charts suggest that our allies contribute more to our mutual security than seen when focusing on military spending alone.

Considering investments in both civilian and military tools of national security might also contribute toward a shared understanding of today’s global threats and what is required to keep America (and our allies) safe and prosperous.